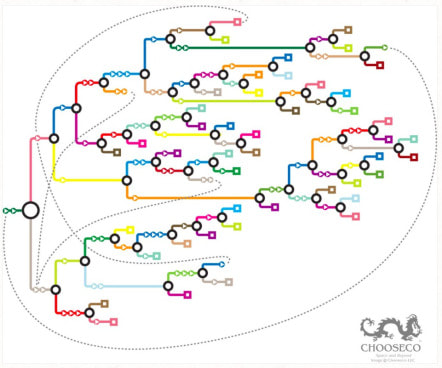

I have always been drawn to art that allows some agency for the audience. It has recently become much more prevalent in the theatre with immersive shows like Sleep No More or Taylor Mac’s 24 Decade History of Popular Music. I had an early formative theatrical experience working with a college troupe inspired by the NeoFuturists’ Too Much Light Makes the Baby Go Blind. The show includes 30 two-minute plays; the numbers 1 – 30 hang on a clothesline across the stage; the audience calls out the number of the play they want to see and the cast pulls that number off the clothesline and performs that play. When that play is over, the audience yells out the next number, and so on. The plays are performed in a different order every night. For bonus fun, there’s a time clock: if the actors finish all 30 plays in 60 minutes, they win “the bet.” If they don’t, the audience wins and gets to whip-cream-pie the actors. The NF plays are each separate entities, there’s no shared story or characters. But I have long been interested in what happens when those short pieces are connected: they exist in the same world, track pieces of the same story. I’ve toyed with that for some time, but never quite figured out the right story. When the idea for Martha’s (b)Rainstorm came along, I had just read a Choose Your Own Adventure novel called Space Vampire! (I highly recommend that everyone read Space Vampires). And suddenly these ideas came together: we are currently making choices for people in the future, by impacting the climate in such a powerful way; doing a Choose your Own Future format story would give the audience agency in choosing, but maintains a narrative aspect. It has been a treat diving into the Choose Your Own Adventure books from my childhood. What strikes me is how stylistically different they can be. There were two primary authors – RA Montgomery and Edward Packard – and their approach to the form is notably different. Montgomery gives new choices every 2 – 3 pages, and there are ultimately more narrative threads, more endings. Packard gives the reader choices every 5 – 8 pages; some threads continue one direction and then meet back with another thread. You have the sense of a single world being explored – reading all the way through one story thread gives you a view of the world that informs the next thread you read. Looking at one of the many maps of the CYOA books shows just how complicated they can get. Doing this format as a play, one consideration is the resources: can actors memorize 32 threads? How do you produce a play that requires so many worlds (props, locations, etc)? What happens if the audience choices lead to death 5 minutes into a performance?

To simplify things I’m ultimately following the Edward Packard style: trying to create a single contained world in which the audience can choose from a few stories: characters and locations will be present in the play regardless of which thread you see, and there won’t be so many dead ends.

1 Comment

|